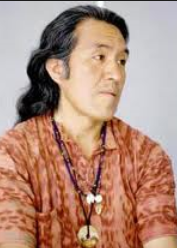

Humberto Ak’abal: poeta maya

Humberto Ak’abal: Mayan Poet

“Me siento profundamente conmovido cuando mi propia gente se acerca para decirme que se siente representada en mi modesto trabajo.

I feel deeply moved when my own people come up to me to tell me they feel represented in my modest work.”

Con los ojos después del mar

With Eyes After the Sea

Humberto Ak’abal, page15.

Although Humberto Ak’abal had been writing poetry about the marvels found in nature for fifteen or twenty years, it wasn’t until the Quincentennial of 1992 that his work was recognized in greater circles, after indigenous needs and rights gained international focus as a result of the meetings held to commemorate the anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the New World. Since then he has become well-known in Europe and moves in international literary circles. Upon paging through his volumes there is an intense love, wonder and amazement for the miracles found in nature. He focuses on the daily life in his village, Momostenango, and explores the cosmic connection between nature and human beings. His poems are short like haikus, often written in his native tongue, K’iche, and lately presented in bilingual editions. He also includes the Mayan glyphs for page numbers in some of his collections, bringing his reality and heritage to the written page. His poetry focuses on his personal experiences of day to day living and growing up in a village.

His first collection of poems, El animalero, was published in 1991. The third edition of this text can be seen here, and according to Gail Ament, “the K’iche word ajyuq, or shepherd, now precedes the original title. Place and date of publication are expressed in three scripts, corresponding to three forms of literacy. First, for the glyph literate, and also for readers who perceive its symbolic effect, the glyph for Iximulew (Guatemala City) and glyphs which give the date of publication are framed within a stela. Second, the same information is given in K’iche written in Latin letters along with dot-and-bar enumeration, to give the date in terms of the Mayan long-count calendar. Translating the numbers to English but conserving the K’iche chronometrical units, this reads as follows: twelve B’aqtun, nineteen K’atun, two Tun, nine Winaq, fourteen Q’ij, ten I’x. Finally, date and place of publication are given as “Guatemala, 6 de octubre de 1995.” (Gail R. Ament, The Postcolonial Mayan Scribe: Contemporary Indigenous Writers of Guatemala, page 166.)

In another collection of his poetry, Con los ojos después del mar, With Eyes After the Sea, Humberto Ak’abal tells his personal history:

“AUSENCIA RECUPERADA

No tuve niñez por la pobreza de mis padres, y la guerra interna del país me robó la juventud. La necesidad de la existencia despertó en mí la responsabilidad del trabajo y aplastó mi temprana edad.

El siglo XXI espera detrás del espejo. Los espejos también muestran lo que hay detrás de uno.

Vienen a mi memoria algunos recuerdos y retazos de mi vida. No es una biografía. Sólo son apuntes que rescato mientras escribo estas líneas.

Desde los seis años de edad comencé a cargar leña, ayudando a mi padre. Tres o cuatro ramas eran mi carga. Ese peso me hizo comprender, paso a paso, la pobreza en que vivíamos.

Fui pocos años a la escuela. Mi padre decía que era importante que aprendiera a escribir mi nombre, para que cuando fuera mayor no se burlaran de mí los que nos minorizaban por ser naturales.

1960. Tendría yo alrededor de ocho años, me acerqué a curiosear algunos libros del profesor de la escuela. Entre ellos había uno que, por el color de las tapas, atrajo mi atención: era amarillento, con el dibujo de dos niños trazados con línea negra; el lomo de color ladrillo. Comencé a hojearlo. Tenía muchas ilustraciones. Leí las primeras páginas y me enamoré del libro. Sin pensarlo mucho, lo robé.

Hice mi primer gran viaje al lado de la biografía del músico alemán Juan Sebastián Bach. Cómo sufrí escondiendo ese libro. Si mi padre lo hubiera descubierto, seguramente me habría castigado. El profesor tampoco supo que fui yo quien le robó su libro.

A la edad de doce años dejé la escuela. De allí todo lo que tengo de estudios es lo que un árbol cualquiera ha hecho en la vida.

Octubre de 1964. Empaqué dos camisas y dos pantalones y me despedí de mi madre. Viajé a la capital para trabajar con un señor a quien mi padre le había pedido trabajo para mí. Vendí dulces y gomas de mascar en la 18 calle.

Algunos días después de mi llegada, descubrí una librería. Se llamaba “La Cadena de Oro”. Al final de cada tarde me iba a parar frente a la vitrina para contemplar los libros. Hubo uno que me llamó la atención. Su portada era la pintura de un rostro horrible. Un rostro como desmoronándose o pudriéndose. Me preguntaba: ¿de qué tratará ese libro? Yo suponía que a lo mejor era algo relacionado con locos, muertos o brujas. Era extraño; me daba miedo y, a la vez, me atraía. Tal vez transcurrieron tres o cuatro meses, hasta que finalmente me atreví a preguntar por el precio. “Dos quetzales con cincuenta centavos”, me dijo el librero. Con mucho esfuerzo reuní el dinero y lo compré. Óscar Wilde y El Retrato de Dorian Gray me llevaron por su mundo los siguientes días. Allí también conocí libros de Dostoievsky y de Stephan Sweig.

Las lecturas de esos libros, al lado de otros a que me he referido en otra ocasión, fueron alimentando mi inconsciente y quizá por eso una noche soñé que había escrito un libro. Al despertar decidí hacerlo. Escribí versos en hojas de papel y las cosí a mano. Anduve de un lado a otro con eso que yo llamaba “un libro”. Hasta que en alguna parte lo perdí y allí terminó aquel juego.

Por esos días se comenzaba a esparcir el rumor de que había problemas en el país. En mi pueblo decían “hay bulla” para referirse al inicio de la guerra en Guatemala.

Estuve poco tiempo en la ciudad. Volví a mi región en 1965. Comencé a trabajar con mi padre, haciendo tejidos de lana de oveja que luego íbamos a vender a la capital. Siete años después falleció él. Yo continué con el trabajo para seguir ayudando al sostenimiento de mi madre y de mis hermanos pequeños.

El reclutamiento forzoso para el servicio militar se intensificó. A mí no me reclutaron porque tengo impedida una pierna. No obstante lo obvio de mi caso, yo tenía que ir a cada poco a la comandancia y cada vez me tenía que bajar los pantalones para comprobarlo. Cómo sufrí esas humillaciones: me tenía que tragar el sabor amargo de la impotencia frente a la prepotencia de los comisionados militares.

Cada vez que yo viajaba, al caer la tarde antes de mi viaje, la mirada de mi madre era una oración y a veces parecía una despedida final. Ella me acompañaba en las madrugadas. Con una antorcha hecha con resina de pino, me alumbraba el camino. Yo cargaba el bulto sobre mis espaldas y, cuando comenzaba a cruzar el puente hecho con dos trozas de árbol, mi madre se quedaba en la orilla conteniendo la respiración. Una vez que cruzaba el puente, ella me daba las últimas palabras y yo me iba a tomar el bus. Cuando recuerdo todo eso, me da escalofrío. Un paso en falso me hubiera llevado al fondo del barranco.

Para ese entonces ya la guerra había abarcado gran parte del país. El trayecto de Momostenango a la capital era terrible. Como en una pesadilla, todos éramos desconocidos. Nadie hablaba en los buses. Uno no sabía quién estaba sentado al lado y, aunque lo supiera, callaba. Callar significaba añadir un minuto más a su existencia.

A lo largo de la carretera presenciamos escenas macabras. En una ocasión vimos en una cuneta los cadáveres como de veinte personas desnudas, filaseadas a machetazos. En otra ocasión, un perro salía del barranco con un brazo humano en el hocico.

Muchas noches no pude dormir. A veces me sentía más seguro cuando estaba nublado: le temía a mi propia sombra. Y no es que yo no supiera del miedo. Sabía de él en el sentido cultural. Soy de la cultura del espanto. De ese algo que sabemos que está ahí, invisible, que convive con uno. Ese algo cuya presencia nos eriza la piel o, que por su fuerza energética, nos hace palpitar el corazón. Per frente a esa realidad que vivimos, el terror hizo palidecer a nuestros espantos.

Uno concebía la idea de irse lejos, pero, ¿a dónde? Muchos lo hicieron caminando y lograron cruzar la frontera del país vecino: México. Otros no pudimos y optamos por escondernos entre la gente. Así fue como volví a la capital y me hice obrero. Trabajé en fábricas. El trato en las mismas no difiere mucho del trato que reciben los campesinos en los latifundios de las costas del país: injusticia y explotación.

Por todas partes se sentía la presencia del terror y del odio. La guerra se prolongaba. Era 1980.

En todo ese tiempo, los libros fueron mis amigos. Comprendí que leer es un acto de humildad. Después de leer un libro, uno ya no es el mismo.

Era difícil la vida en aquellos días. Mi rostro se tornó áspero por la sal de las lágrimas.

Comencé a escribir algunos poemas en los que sentí la necesidad de volver a mi infancia. Recupero, o mejor dicho, intento recuperar en cada texto esa niñez que tuve. Intento recuperar aquel pueblo que caminé de arriba abajo haciendo mandados, o, simplemente por el gusto de caminarlo, bajo el sol o bajo la lluvia. Intento también recuperar esos años jóvenes que se marchitaron desgastándose en el trabajo.

A veces me preguntan: —¿Cómo se siente un hombre que no fue niño? —Con hambre, he respondido. Por eso amo mis recuerdos. Así es la pobreza, lo obliga a uno sentirse adulto aunque sea niño y sólo comprende la diferencia cuando las fuerzas se le acaban antes de la caída del sol.

Escribo en primera persona porque no soy nadie para hablar en nombre de los demás. Y me siento profundamente conmovido cuando mi propia gente se acerca para decirme que se siente representada en mi modesto trabajo.

Tengo claro la idea que mi poesía no es ninguna revolución en la literatura guatemalteca ni en el mundo. Pero también estoy consciente de que no soy un hongo que brotó de la noche a la mañana. Hablo y escribo sin rencor ni amargura. Lo que hago, lo hago con el corazón.

Viena, otoño de 1999

Con los ojos después del mar

páginas 9-15

RECOVERED ABSENCE

I didn’t have a childhood because of my parent’s poverty, and the internal war in my country robbed me of my youth. The need to merely exist awakened my responsibility to work and crushed my early years.

The 21st century waits behind the mirror. Mirrors also show what’s behind you.

Some memories and fragments come to mind. It’s not a biography. These are notes that I bring to life as I write these lines.

From the age of six I started hauling firewood to help my father. My load was three or four branches. Step by step, the weight made me understandthe poverty in which we lived.

I went to school for a few years. My father said it was important for me to learn to write my name so that the people who put us down for being down to earth wouldn’t make fun of me when I was older.

1960. I must have been around eight years old, and I took a closer look at some of the teacher’s books at school. There was one that, because of the color of the cover, attracted my attention: it was yellowish, with a drawing of two children outlined in black, and the spine of the book was brick colored. I started leafing through it. It had a lot of pictures. I read the first few pages and fell in love with the book. Without giving it much thought, I stole it.

I took my first long trip with the German musician, Johann Sebastian Bach’s biography next to me. I suffered so hiding that book. If my father had seen it, he surely would have punished me. The teacher didn’t know I was the one who had stolen the book either.

I quit school when I was twelve. From then on the only studies I have are the ones that any tree has made of life.

October, 1964. I packed two shirts and two pair of pants and said goodbye to my mother. I traveled to the capital to work with a man my father had asked to give me a job. I sold sweets and chewing gum on 18th street.

A few days after my arrival I discovered a bookstore. It was called ‘The Golden Chain’. At the end of the day I would stop in front of the shop window and contemplate the books. There was one that really stood out to me. There was a painting of a horrible face on its cover. A face that was falling to pieces or decaying. I asked myself, ‘What could that bookbe about?’. I imagined it might have something to do with crazy people, the dead or witches. It was strange; it scared me, and at the same time I was attracted to it. Probably three or four months went by before I got up the courage to ask about the price. “Two quetzals and fifty centavos”, said the shop owner. With a lot of effort I got the money together and I bought it. Oscar Wilde and The Portrait of Dorian Gray transported me through their world for the next few days. There I also became familiar with books by Dostoyevsky and Stephan Sweig.

Reading those books, and other books that I’ve referred to on other occasions, nourished my subconscious and may be the reason that one night I dreamed I had written a book. When I woke up I decided to do it. I wrote verses on pieces of paper and sewed them together by hand. I carried my so-called “book” all over the place, until I lost it somewhere and that’s where the game ended.

Those were the days when rumors that there were problems in the country started circulating. In my village they would say, “There’s uproar” to refer to the beginning of the war in Guatemala.

I wasn’t in the city for long. I returned to my region in 1965. I started working with my father, making weavings out of sheep’s wool and taking them to the capital to sell. Seven years later he died. I kept on working with the weavings to support my mother and my small siblings.

Mandatory recruitment for the military intensified. They didn’t recruit me because I have a stunted leg. Even though my case is obvious, I had to go to the headquarters frequently and each time I had to pull my pants down to prove it. I suffered those humiliations so deeply: I had to swallow the bitter taste of powerlessness in the face of the military commanders’ prepotency.

Every time I traveled the look on my mother’s face the night before I left was a prayer that sometimes seemed like a final farewell. She would accompany me in the early mornings, lighting the path with a torch made from the resin of a pine tree. I carried my pack on my back, and when I started to cross the bridge consisting of two tree trunks, my mother would stay on the shore holding her breath. Once I had crossed the bridge she would say goodbye and I would go to take the bus. When I remember all this it gives me the chills. One wrong step would have taken me to the depth of the ravine.

At that time the war had extended into most of the country. The trip from Momostenango to the capital was terrible. We were all strangers, like in a nightmare. Nobody talked on the buses. You didn’t know who was sitting next to you, and even ifyou did know, you kept quiet. Keeping quiet meant adding another minute to your existence.

Along the highway we witnessed macabre scenes. Once, on one of the shoulders we saw the cadavers of about twenty people, naked, with machete cuts all over them. On another occasion a dog came out of the ravine with a human arm in its mouth.

Many nights I couldn’t sleep. Sometimes I felt more secure when it was cloudy: I feared my own shadow. It’s not that I didn’t know about fear. I knew about it in a cultural sense. I’m from the culture of terror. There’s something that we all know is there, invisible, something that lives with you. It’s something whose presence makes our hair stand on end, or because of its energy force, makes our heart beat faster. Having lived the reality we lived, terror faded our fears.

One toyed with the idea of going far away, but where? Many left on foot and were able to cross the border of the neighboring country, Mexico. Some of us couldn’t and we opted for hiding amongst the people. That’s how I went back to the capital and became a laborer. I worked in factories. The treatment there wasn’t very different from the treatment the peasants receive on the large coastal estates and farms: injustice and exploitation.

The presence of terror and hatred could be felt everywhere. The war continued on. It was 1980.

During all that time books were my friends. I learned that reading is an act of humility. After reading a book, you aren’t the same anymore.

Life was difficult in those days. My face became rough from the salt of my tears.

I started writing some poems in which I felt the need to return to my childhood. In each poem I recapture, or try to recapture, the childhood I had. I try to recapture the village that I walked all over doing errands, or, simply just walking for pleasure of walking in it, under the sun or under the rain. I also try to recuperate those youthful years that died away, worn away by work.

Sometimes they ask me: “How does a man that wasn’t a child feel?” “Hungry”, I’ve responded. That’s why I love my memories. That’s how poverty is, it makes you feel like an adult even though you’re a child and you only understand the difference when you your strength runs out before the sun goes down.

I write in first person because I’m not one to speak for others. I feel deeply moved when my own people come up to me to tell me they feel represented in my modest work.

I’m sure that my poetry isn’t any revolution in Guatemalan literature or in the world. But I’m also conscious that I’m not a mushroom that just appeared one day. I speak and I write without resentment or bitterness. Whatever I do, I do it with my heart.

Vienna, fall of 1999”

Con los ojos después del mar

pages 9-15